The Concerned Artist's Guide to AI Art

Images, unless otherwise noted, were generated using Stable Diffusion, an AI model.

What is Art?

Prompt: 'Things that are not Art'. Thank goodness the AI knows what is and isn't art. I guess that settles it and you can stop reading now.

If there is one thing my bougie liberal arts education prepared me for, it is to recognize that anytime anyone asks, “What is art?” it is a trap. Lucky for me, I am not trying to argue whether or not AI generated images are art. This gives me an easy out: for the purposes of this article, art is whatever you think it is.

I’m going to write a bit about what people have thought art was in the past, and about what AI-generated art is and how it works. After that, I’ll leave it up to you to decide for yourself whether or not these computer-generated images can be considered Art-with-a-capital-A.

The AI Painting that Launched a Thousand Tweets

AI image generation has improved at an absolutely bonkers pace over the last few years, but for many, the incident that launched it into the public sphere for debate was a Colorado man named Jason Allen winning first place in an art competition at the State Fair with his AI-generated painting, “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial.”

Théâtre D’opéra Spatial by Jason Allen, generated using Midjourney

Nevermind the fact that before now, as far as I’m aware, the general population of the Internet has never cared about a State Fair art competition. Allen’s win has prompted dramatic statements declaring it “the death of artistry” and the “end of art as we know it.”

So, is it?

The Death of Art

This is far from the first time an emerging technology or cultural shift caused someone to proclaim the Death of Art. In the mid 1800s, poet Charles Baudelaire wrote, “If photography is allowed to stand in for art in some of its functions it will soon supplant or corrupt it completely thanks to the natural support it will find in the stupidity of the multitude.”

Clearly, art continued to be created beyond the 19th century. However, that doesn’t mean that photography did not affect art. Many of the art movements and trends that came after forsook realism in favor of abstraction and more extreme stylization. Also, photography came to be recognized as an artistic medium in its own right.

In at least one case, photography did make an entire profession of artists obsolete. Prior to the camera, it was common to have a portrait miniature painted, and many artists made a decent living as miniaturists. Although photography likely created more jobs than it destroyed in the long run, that would have been of no comfort to the miniaturists living during that time who lost their livelihoods, whose skills did not translate to the new technology.

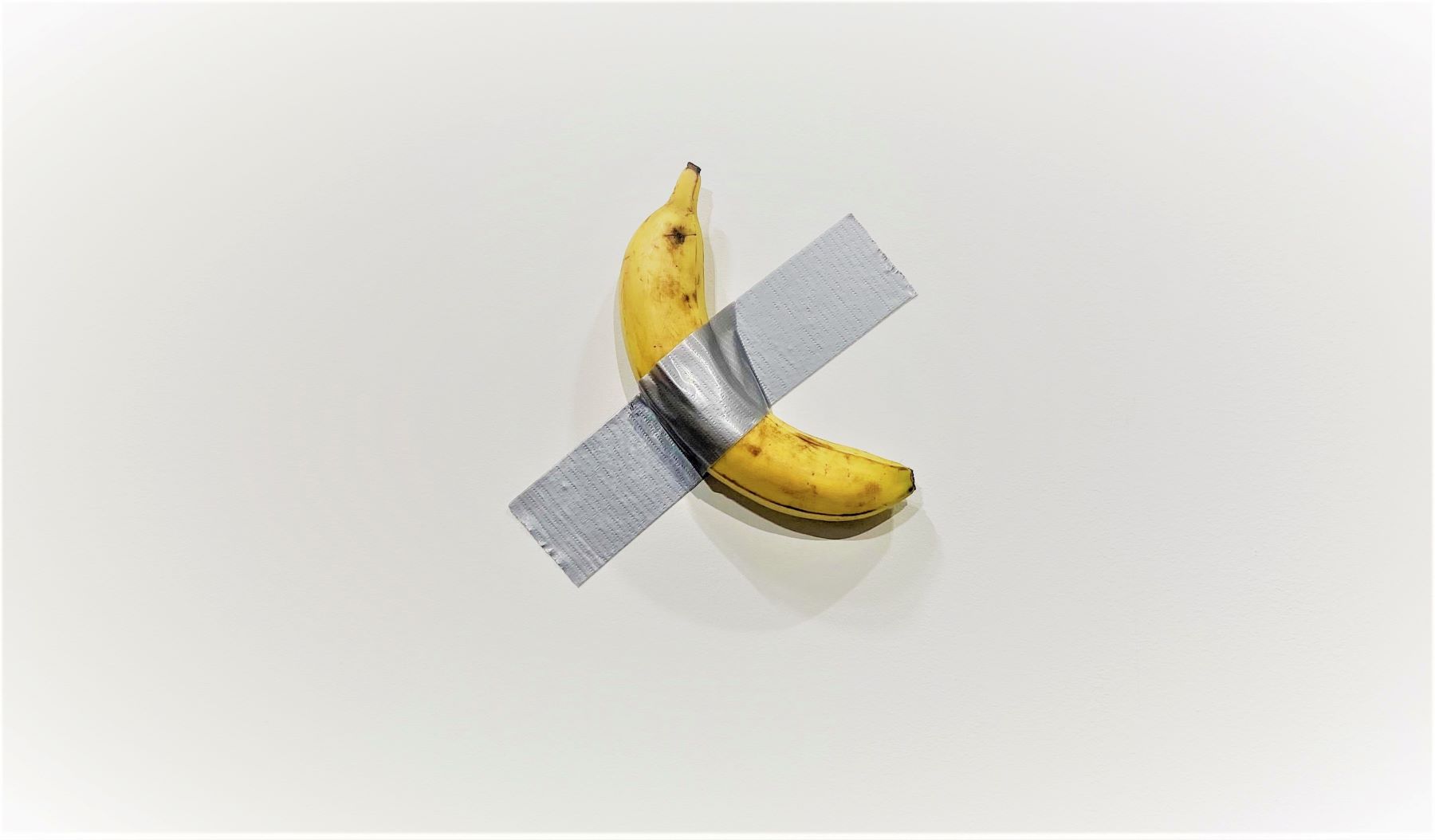

In spite of, or perhaps because of the fact that it is the most trite and overused example in all of Western art history, I think I’m obligated to mention Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’—aka another time people started predicting the demise of art. For the unfamiliar, Marcel Duchamp upset the art world in 1917 when he submitted a urinal to an art exhibition. Many said it was not art, since the artist had not created the piece, and had merely slapped a signature on a piece of plumbing. Many of the trends and movements in Modern art have faced similar critique—with people wondering if art that is purely conceptual can really be considered art, especially if it requires no particular training, skill, or technique on the part of the artist.

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, for sale for over $100,000 at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2019. Photo by Sarah Cascone. Shamelessly stolen by me.

Form vs Content

Art is often thought of as the union of Form and Content. Medium and Message. Different movements throughout history have favored them in differing proportions. Prior to the 1900s, as far as I know, form was always at least as important as content, if not more so. It didn’t matter how good your concept was; you needed a mastery of skill and technique to be considered an artist. Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ was the opposite end of the spectrum—almost no skill, heavy on message.

A lot of the criticism of Modern art can be summed up as “Hey, my 5-year-old could have made that!” AI-generated images occupy the other extreme of the spectrum. These models (that’s what we call the programs that make AI art—more on that later) are often unnervingly good at mimicking techniques and styles. In a matter of minutes, an AI can generate an image that would have taken a human years of study to develop the skill to produce, and weeks of effort painting. However, these images don’t have any intrinsic message or meaning. It would be reasonable to think of them much as the urinal on the shelf before it has been chosen as a vehicle of art. They simply look like they require a surfeit of skill to produce, unlike the urinal which is very obviously a mass-produced object.

I don’t think we can ignore one of the unique traits of AI art—how well it mimicks a skilled human artist. Even if technique is not in and of itself enough to constitute art, skills at painting and illustration that may be honed during an artist’s career are useful in a number of professions, not unlike the miniaturists of yore.

The Starving Artist

The majority of artists do not make a living wage from their work. At its highest levels, art appears to mostly be valued by the ultra-wealthy for tax-related investment purposes. With such a sense of competition and scarcity, it’s not surprising that some artists have a gut reaction of paranoia, despair, or disdain toward AI-generated art.

Many artists are able to use their artistic skills in professions such as graphic design, stock illustration, and tattooing. It does not seem unreasonable to suppose that AI-generated art poses a threat to these professions, particularly to artists who are not technically savvy. A stock illustration does not need to have an original point-of-view or message for the world. It can be (and often is) completely soulless. If a computer can generate a reasonable facsimile of “man yelling at a duck, flat vector illustration” or “wide-angle close up of backlit keyboard,” there’s no reason to have a person make it. Why care about the original style of your tattoo artist, if you can just describe what you want and the computer can design 20 options for you to choose from in under ten minutes?

Sometimes, instead of learning skillfull techniques valued by humans, however, the AI models learn about things like stock image watermarks. It's useful to be aware that AI is not consistently churning out masterpieces.

It’s not exactly as if these are all new problems—but AI-generated art makes them more acute. A lot of websites use stock art and photography without paying for it or giving credit, and software for removing watermarks has already been around for a few years. AI has not created the problems; they are societal, systemic. AI-generated art may, however, enable us to further devalue artistic skill. It is not a trivial fear.

Beyond the fear that AI art may take away artists’ jobs and get rid of the need for skill in creating art, the other common worry is that AI art is copying and stealing from other artists. To address that concern, it will be useful to have a basic understanding of how the images are generated.

I’m a Model, if You Know What I Mean

A lot of the state-of-the-art image generation that is done right now is done using Diffusion Models (DMs). Given how quickly the field is moving, it’s quite plausible that won’t be case by the time you’re reading this. A model, as far as deep learning is concerned, is used to refer to algorithm (how it works) + data (what it’s been trained on). There are a number of different models that use diffusion (an algorithm), but because they were each trained on different images (the data), or with different parameters, they produce different output.

The first, and really the most important step, in creating a generative model is training. This part is invisible to anyone who is using these tools just to create images—and, at the scale of big, high-quality models like DALL-E and Stable Diffusion, not accessible to the average person. During training, the models are exposed to billions of text and image pairs, running on the data for many iterations, learning the features of what makes an image. Between the specialty hardware and electricity costs to run such intensive computation, training one of the big models can cost hundred of thousands to hundreds of millions of dollars.

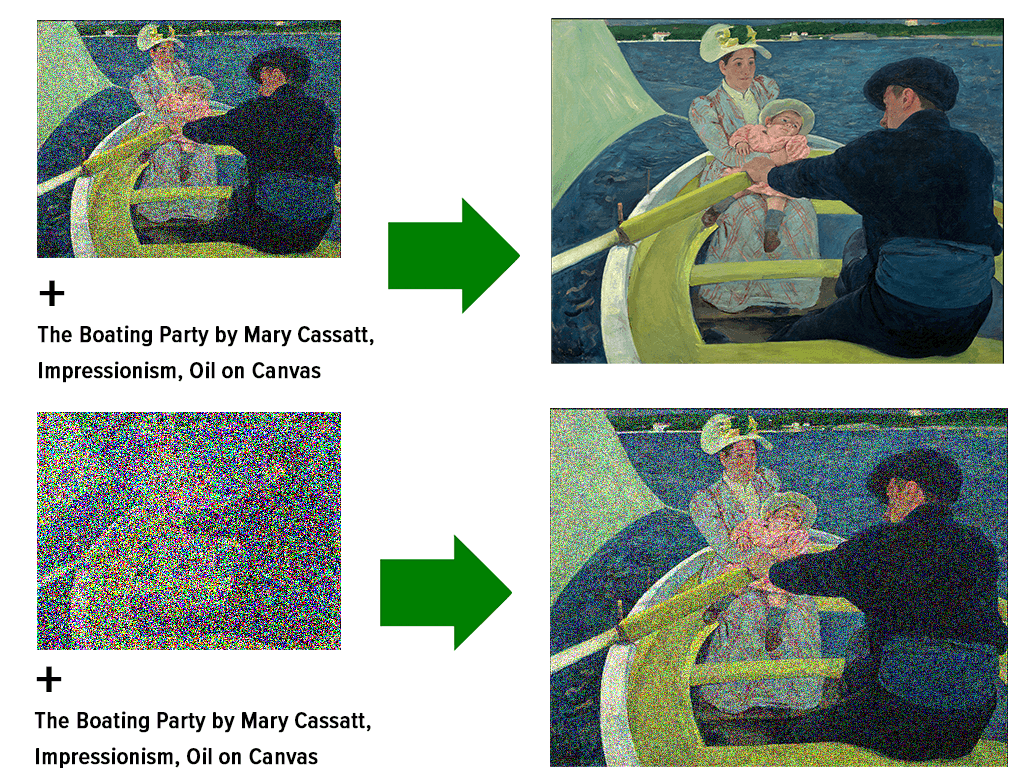

I’ll stick with Diffusion Models for my examples, both because they are currently en vogue, and because I think they are clever. During training, a DM is learning a very particular skill—how to “de-fuzz” an image in iterative steps. It is learning how to take a slightly blurry image, and turn it into the original image, and how to take an even blurrier image, and turn that into a slightly blurry image, and so on and so forth, until it’s learning to take completely random noise, aka static, and turn that into a normal picture. Along the way, it’s guided by a text caption, so it’s also learning how that relates to the final image.

A fast-and-loose simplification of what a diffusion model learns. In a certain sense, it's just a fancy image de-noiser.

Once trained, the generative aspect comes into play because the model is being fed random noise as the starting image, rather than noise that was developed from progressively fuzzing an original image, and it is being given a prompt that it has quite possibly never seen before. The combination of the two is pretty much guaranteed to be novel, so the model is forced to generate something original. The generation itself is not random—the randomness comes from the starting image (static noise, generated randomly) and the guidance of the prompt. Given the same “seed,” which is to say, the same starting noise, and the same prompt, the same model will always generate the same image.

The human element in the whole endeavor comes down to honing prompts that create interesting or appealing output, and running them many times until a seed is found that also results in a cohesive, aesthetically-pleasing image.

Techno-optimists see these kinds of deep learning models as a move towards computers learning to think like humans—to self-construct meaningful neural connections. Techno-skeptics think of them as complex equations that we are figuring out how to solve by throwing darts at a wall, with our progress mostly tied to being able to throw as many darts at once as fast as possible.

So how does this tie in to the main question that we’re trying to answer: are the images produced by these generative models copying and ripping off artists’ work?

One line of thought is that these models are attempting to replicate the way that humans learn—they are building deep, inscrutable connections between things (in this case, a visual vocabulary) and learning to recognize underlying patterns. Humans learn to create art by studying art. At first, children may begin by copying existing drawings. With time and practice, the artist learns a variety techniques and styles, and begins applying them in novel ways and in original combinations, creating a personal style that is no longer derivative, but something new. Creativity does not just emerge from the void, pure of context and precedent. By this line of thinking, AI art is no less original than what humans create; influenced and inspired by what has come before, reinterpreting it in a new way.

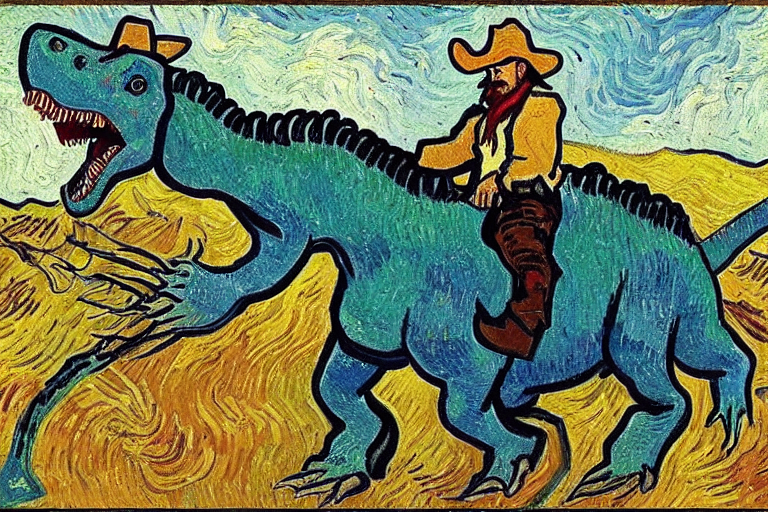

Conversely, it’s possible to argue that the AI only has the influence of the other images it has seen, whereas the human artist also has personal and cultural context at play. When you ask the AI model to create “Cowboy riding a dinosaur, by Vincent van Gogh,” its intrinsic goal is to make the most accurate possible replica of what Vincent van Gogh would have painted, if he had painted a cowboy riding a dinosaur. The AI is not trying to pick out what it thinks are the most interesting or beautiful aspects of van Gogh’s style—it has no opinion, it is merely trying to use its knowledge of what van Gogh paintings have in common in order to apply those to a new subject. By this line of thinking, one of the necessary components of art is the element of personal choice and judgment—such as the artist choosing what parts of van Gogh’s style are essential to emulate in order to convey a specific effect.

Prompt: 'Cowboy riding a dinosaur, by Vincent van Gogh

Prompts & Models IRL

Show, don’t tell, or so I’ve been told. I’ve put three related prompts to three different models to show the effect of each. VQGAN+CLIP was hot and sexy in 2021—I wasn’t kidding when I said that progress was moving at a bonkers pace. DALL-E Mini and Stable Diffusion are both diffusion models, both released in 2022. DALL-E Mini had about 15 million training images. Stable Diffusion used 5 billion.

Three different prompts, by three different models. Row 1: VQGAN+CLIP, Row 2: DALL-E Mini (Craiyon), Row 3: Stable Diffusion. Prompts, from left to right: 'A dinosaur at a birthday party', 'A beautiful painting of a dinosaur at a birthday party, trending on artstation', and 'An illustration of a dinosaur at a birthday party by Edward Gorey'.

I think all three models have their charms. VQGAN isn’t about to supplant any human jobs—its output is nightmarish, but interesting. Like DALL-E Mini, it only had tens of millions of training images, but it uses a different kind of network. I appreciate its dreamlike, surreal qualities, and have found it fun to play with.

DALL-E Mini has very little in common with DALL-E, for which it was named. In fact, it has recently renamed itself “Craiyon,” and I would be willing to hazard a guess due to copyright/trademark. Both are diffusion models, but DALL-E mini was created by a single individual, with a different architecture and far fewer training images. It’s pretty good at literal interpretation of the prompt, but its output is a bit blurry and lacking in detail.

Stable Diffusion is currently, as of September 2022, “hot shit.” It is what is known as a Latent Diffusion Model. Explaining what that means is beyond the scope of this article, but the TL;DR of it is that Stable Diffusion uses something known as “latent space” to provide state-of-the-art results with a fraction of the requirements in terms of GPU and memory. It’s fast. It can run on a fairly normal computer. It was trained on an absolutely massive dataset. Unlike DALL-E 2, which is also “hot shit”, it is free and open source.

Try it for Yourself

The best way to get a feel for what AI art is—and isn’t—is to try your hand at making it. In my experience, getting a truly high quality image takes a fair amount of practice and persistence. Prompt-tuning, that is, figuring out the right combination of words and modifiers to get the output you want, is an art in and of itself, regardless of whether you believe that AI images are art or not.

Craiyon - Probably the most dead-simple way to get started. The images are small and low-quality, but it’s fast and free. It’s quite high-tech, despite its limitations.

Midjourney - I haven’t actually used it, and the tool is still techinically in beta; you’ll have to request an invite to make an account. It combines state-of-the-art AI with a user-friendly interface. Some very cool works, including the state fair winning image, have been generated with Midjourney.

Disco Diffusion - This requires you to go close to code, but I promise it’s not as scary as it looks. It uses something known as a “colab notebook”—it’s basically an easy way for sharing code that you can run on a Google Cloud server. It’s free for a basic account, although you can upgrade to a paid account to guarantee access to machines with better GPUs. I’ve used this a lot—one bonus is that there’s a big community around it, with lots of tutorials, documentation, and advice.

Stable Diffusion - Another colab notebook. A little less user-friendly than Disco Diffusion, but should be do-able even for the non-technically savvy with a little practice and patience. It makes images much, much faster than Disco Diffusion does. I would say that the results are much better at understanding complicated text prompts and creating “semantic” images than Disco Diffusion, but I actually still prefer Disco Diffusion when it comes to things like applying additional artist styles, e.g. “A beautiful painting of a donut, by Frida Kahlo and Peter Max.”

Take Home Test

I meant it when I said that I wasn’t going to tell you whether or not AI-generated art is Art. That’s something you have to decide for yourself. I will, however, leave you with a few questions for discussion or reflection.

- In what ways is the emergence of AI-generated art comparable to the advent of photography? In what ways is that analogy not applicable?

- Is it fair to compare the AI artist to the artists producing “readymades”, like Duchamp’s “Fountain”? Why or why not?

- I have only focused on U.S. and Euro-centric art history and reactions to AI art. How do you think different cultural values might effect the perception of AI art? Extra credit: actually search for articles on the subject from a non-American/European source.

- Let’s say you’ve got a painting in your living room. It really ties the whole room together, kind of like the rug did for the Dude in the Big Lebowski. You also have a charming anecdote about the artist who made it that you love to tell guests when they come over. At some point, you find out that the person who sold it to you had lied: it’s a computer-generated painting, printed on canvas, one of a run of hundreds of this particular print. Questions of “is it art??” aside, do you still leave it up in your living room? Does your attitude toward the painting change?

- What is art’s role in modern society? Is it still relevant? Is it possible for art to become irrelevant, e.g. die? Describe a world in which art is dead.

Comments? Corrections? Thoughts? 👉Shoot me an email: nome@nome.codes